There is no one for me to talk to about this film,

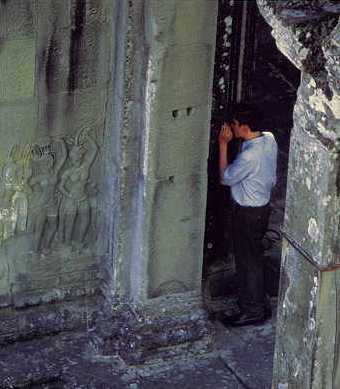

so I am putting this review in a hole in a wall

and covering it with mud and straw.— Cold Bacon, 2000

"There is nothing but emptiness, the empty existence I exchanged for the truth."

“In the bald and barren north, there is a dark sea, the Lake of Heaven. In it is a fish which is several thousand li across, and no one knows how long. His name is K'un. There is also a bird there, named P'eng, with a back like Mount T'ai and wings like clouds filling the sky. He beats the whirlwind, leaps into the air, and rises up ninety thousand li, cutting through the clouds and mist, shouldering the blue sky, and then he turns his eyes south and prepares to journey to the southern darkness.

The little quail laughs at him, saying, 'Where does he think he's going? I give a great leap and fly up, but I never get more than ten or twelve yards before I come down fluttering among the weeds and brambles. And that's the best kind of flying anyway! Where does he think he's going?" Such is the difference between big and little.” - From The Chuang Tzu

|

- From Donald Barthelme's, Eugenie Grandet |