Once Upon A Time In The West (2001)

Sergio Leone: Guy Laroche of the Desert, Guy Laroche Rides Again, Say It With Rope, Sea Cucumber

The first time you look at any great work of art, you can never fully realize all of the small and seemingly innocent details therein. But then over time you begin to notice how they are indeed there, so many of them, and you wonder if it is not the very multitude of these details that makes a thing great.

Once Upon A Time In The West, a film by Sergio Leone, bears watching for as many times as you can do. Because it will never cease to yield new pleasures, new details. Here are some of the ones I have found.

But They Were His Men?

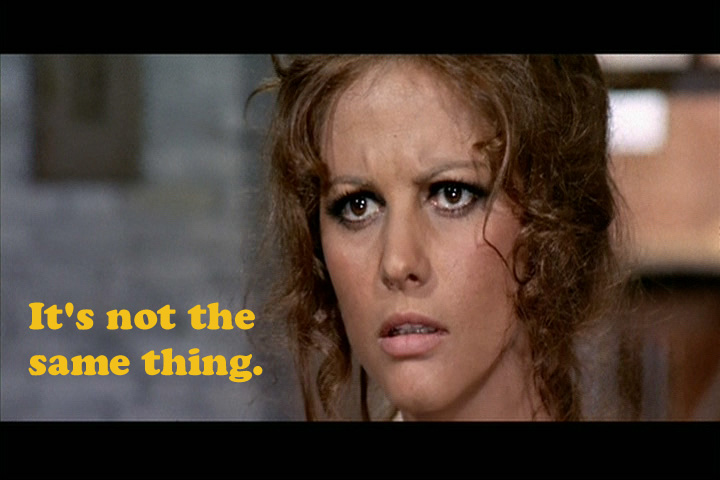

Among others, one scene that really accentuates the three dimensionality of Jill’s character is when Harmonica has just shot a bunch of Frank’s man and in so doing, actually saves his life.

Jill: “But they were his men? And you, you let him get away.”

Harmonica: “I didn’t let them kill him and that’s the same thing.”

Jill: “Sure, it’s not the same thing.”

It’s actually unclear, from the way she says it, whether she agrees, or rather, whether she approves of Harmonica’s decision. We know Jill is smart enough to understand the situation and figure out why Harmonica does this, but the question is whether she really is okay with this. Remember, she, or at least a part of her, wants Frank dead as much as anyone. In any case, by exercising political opinion, ambiguous or not, she perpetuates her status as a character as vital to the film as any. When does this happen in a Western? Where the female “love interest” is both this integral and this hot? The women in Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch are either whores or village hens. You’ve got two choices. And nevermind Peckinpah’s misogyny. What’s worse, having a memorable whore (if you’ve seen Wild Bunch, you’ll vividly recall that young wife who hitches up with the general—her purple satin dress, tan Mexican skin, lipstick, big adulteress grin right before—?), or having some cookie cutter heroine whose main function is to look scared, wear a check blouse, and hug the hero at the end. In Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, the lead female role is the memory of his wife urging him to change his violent ways. Not exactly what I would call a challenging character. Of course, Leone himself, in his earlier films, was the worst. In The Good The Bad The Ugly, I don’t even think we saw any women at all. And before that, women had such dynamic roles as serving cornbread and providing some of the reason why all the men keep killing each other.

Strictly A Need To Know Basis

One of the more peculiar aspects in Once is the strange three way relationship that develops between Harmonica, Cheyenne and Jill. The two men hatch a plan to rescue Jill by buying her property right out from underneath Frank’s nose. Of course, they don’t bother to mention it to Jill. Instead, they just leave her completely in the dark up to the very last moment. Harmonica does Jill the same in an earlier scene when he has her, “Get me some water. From the well—” only telling her to duck at the last second, but not explaining beforehand. The simple explanation is that this is a way of ensuring people (Jill) do what they’re supposed to and don’t tip their hand. Like pawns in a chess match. The last thing you want is for them to know what’s going on. Or one might want to read some kind of sexist undercurrent here, except it’s the same thing we saw in The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly when Clint Eastwood sadistically waits until the very last moment to save his partner, a man. And it’s not just the players, we ourselves get the exact same treatment from Leone. When Cheyenne is suddenly rerouted to a different jail, we genuinely worry about his fate. Leone totally leaves us hanging for a minute.

We Have All Known Each Other Forever

Throughout Once, there is a sense of shared history between all of the major players, which goes beyond and before the just what transpires on the screen. For example, when Frank talks to Jill as he caresses her

“I wonder if McBain knew he married a whore. Yeah, I’ll bet he did know. It was always like McBain.”

This clearly suggests a prior relationship between Frank and McBain, which is only alluded to rather than explicitly revealed. And this is much better. It’s like in Star Wars when the Millennium Falcon sticks onto the star destroyer in order to avoid detection by their radar. And the Emperial commander says, “No ship that small has a cloaking device!” Oh god. Here, it’s not a personal relationship but a suggestion of shared common knowledge, which allows us to use are imagination. But we expect this sort of thing in science fiction, like Star Wars or Dune. Really not so much in Westerns, at least, until Leone.

When Cheyenne has only just met Harmonica in the stable, he speaks to him with an affection as though he has known him a long time. And when Frank meets Harmonic on the train.

“So you’re the one who makes deals.”

“And you’re the one who doesn’t keep them.”

They refer to the opening sequence of the film, wherein some arrangement had been made between the two. Here, the allusion is explicit. Nevertheless, it works to establishes the notion of shared history early on. Later:

“Pick any method you like. Just make the deal.”

“Which deal frank? We have more than one you and me.”

And when Harmonica says, “Easy Frank. You gotta learn not to push things.” The beautiful thing is how he says it in that wickedly condescending tone. Again, building on this idea of personal history between the two, which Frank, for the life of him, literally, cannot remember.

Frank: “Surprised to see me here?”

Harmonica: “I knew you’d come.”

Leading up to the final showdown, as Frank rides up to Harmonica who waits for him, “whittling on a piece of wood.” Notice the tiny little hint of a smile he shows. Perhaps this is showing that small amount of respect he feels for Frank. Not before, but now. By making the choice he has made, to confront and live down his past. Frank has elevated himself in Harmonica’s eyes.

Harmonica: “So you found out you’re not a businessman after all.”

Frank: “Just a man.”

Harmonica: “An ancient race. Other Morton’s will be along, and they’ll kill it off.”

Frank: “Don’t matter to us. Nothing matters now, not the land, not the money, not the woman. I came here to see you. Cause I know that now you’ll tell me what you’re after.”

Harmonica: “Only at the point of dying.”

Frank: “I know.”

Say It With Candlesticks

Near the end of the film, Cheyenne talks with Jill as she sets the table in the background. She lays the table cloth out and begins flattening it. He tells her he doesn’t think Harmonica is the right man for her. The camera then shows us Cheyenne’s face as you hear in the background a heavy clunking sound, which must be the candlesticks being placed on the table. It becomes clear that thud we hear is her unspoken response to Cheyenne’s pessimism, which is a resigned yet dissatisfied acceptance. It’s a fairly straightforward tactic by Leone, but the noise, the exact noise and the action it represents expresses her feelings more precisely and entertainingly than any bit of dialogue ever could.

God Damn It’s Bright Outside

The other main point about all of these films is the bright sunshine. My god there’s a lot of it. And it’s all this wonderful yellow and brown, dry and hot kind, which you can almost feel. That’s one of the obvious but possibly overlooked wonders of all true Westerns. Real widescreen tonics.

One particular element in Once, which also happens a lot, if I remember, in The Searchers, is this very surreal contrast between daytime and night. Oh, and it happens a lot in a Peckinpah film Pat Garret & Billy The Kid. But that abrupt transition from extreme light outside to extreme dark inside when for example Jill stops off at the ‘general store’ on the way to the Sweetwater. Sort of like when you go into and out of a movie theatre on a bright sunny day. That first moment when you open that door, and you’re hit with that facefull of light. Wow. That’ll stop you.

Getting Into The Mind of That Minor Character

Remember the scene where Cheyenne gets into that moving train shootout with some of Frank’s gang. During the scene there is that worn technique of letting us experience the action from the perspective of the minor character who is about to be killed. It could be some unfortunate German terrorist, Rolf, about to do exactly what Bruce Willis wants him to. Or it could even be one of Thulsa Doom’s long-haired beauties about to impale himself on a truly brilliant trap set by Conan the truly brilliant Barbarian. The common thread in all of these instances is that the amount of time we spend inhabiting the doomed minor character is usually no more than fifteen seconds. But here, I can promise, you it’s a lot longer than that.

And as we watch Frank’s man take that slow walk through the traincar as he is stalked by Cheyenne, we have plenty of time to develop the keenest sense of shared identification with that quite justified look of fear he’s got on. It’s that same “Ueuhh, how did I get into this?” we see in both great films—the final duel scene in Barry Lyndon—and not so great films—Gladiator—when the newbees get their first taste, or I should say, face full of the arena.

But Leone makes it even more fun by having Charles Bronson just stand there and watch the scene unfold. He looks just as intrigued as we are. Bronson as spectator (and stand in for us) is risky in coming dangerously close to breaking the suspension of disbelief. But the risk pays off big as it creates a remarkable and strange emotional situation for all of us. And not only that, but it’s perfectly in keeping with Bronson’s almost Malkovichian character, who is already odd enough by his quirky grammar, his unexplained behavior (e.g. his seemingly random rape overtures with Jill), and just the fact that he gets shot in the first scene (for crying out loud). Not your average, everyday hero. Remember how Tuco wears his gun around his neck on a string. Oh god.

And then there is the stunning depiction of McBain’s agony at the sight of his felled daughter. His desperation brilliantly filmed, as he runs for the chair where his gun is. At this moment, he cares about nothing else, not the money, not his dreams, nothing. Just a girl, his daughter. And that is gripping. I don’t care what anyone says.

Romance, Perspective

In most Westerns, the final shootout scene take place in some private, secluded place. The two heroes battling it out, their isolation underscoring their lonely and heroic lot. Bla bla. But here, the duel will take place right in the midst of droves of railroad workers. The workers, who represent modern society and progress, are physically present, but simply could care less about the activities of these two eclipsed individuals. In this way, Leone rather emphatically highlights the discrepancy between personal, appropriately irrational goals versus the cool advancement of society as a whole. And so we may still choose to sympathize with the hero, to reject society, reject Microsoft, cell phones, Starbucks, the EU. But we must do so, thanks to Leone, having seen there is another side to it, a side which totally doesn’t care.