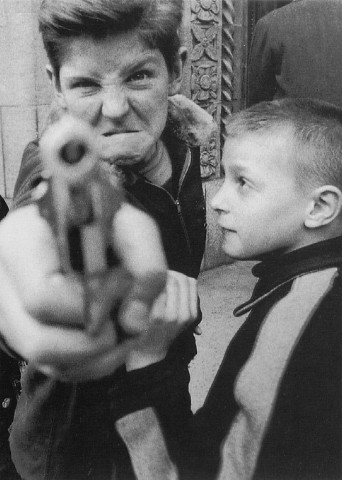

Guns are bad. According to Michael Moore, bullets are even worse. The main premise of Bowling for Columbine is that if we could take all the bullets and turn them into little chocolates and give them to Michael Moore, then he would be happy. But we don’t because we’re a bunch of assholes who want to horde all the chocolate for ourselves. There are about 11,000 gun deaths annually in the United States (five involving disputes of or relating to chocolate). This compares to roughly one hundred (two chocolate) in each of the major European countries (not counting Belgium). Okay, wow. So gun violence is a huge problem in this country, second only to Michael Moore and his brand of manipulative polemic. Bowling for Concubine uses the power of documentary to make you sympathize with the characters it wants you to and despise those whom Moore thinks stole his Godiva four-pack. Somebody stole it. They had to have. It’s gone isn’t it?

From a stylistic point of view, Moore’s attacks often seem mean-spirited and out of touch. When he goes after the poor Kmart employees, it’s like he’s attacking Peggy from King of the Hill. I mean come on, she just works there. You end up feeling as sorry for Kmart as anyone else. Although I must say it was inspiring to see Kmart promise to stop selling ammunition to nine year-olds by 2027. The film goes to some trouble to prove once and for all Charlton Heston is a gun toting racist. Thank God we finally cleared that one up. But Moore cheapens his victory by running up the score on an opponent who obviously suffers from Alzheimer’s. The greatest threat Charlton Heston currently poses is to the world of interior design. My Lord, that awful ranch house with those sliding glass doors and faux rock walls. I wonder where he keeps all his guns. I didn’t see any. Did you see any? Moore should realize a good case will make itself without having to resort to cheap tricks like those subliminal images of nuns being spanked by men that looked just like—oh my, wait a minute. Is there nothing Limbaugh won’t try?

As a persuasion film, Bowling suffers from some very shaky analysis. The film seems bewildered how Canadians could have as many guns as we do but no murder. Hello. They have no crime. They have no people! If we had two acres a person, I seriously doubt we would have any crime either. In order to kill someone, you first have to be able to find someone. They’d have to take a two day dog sled, and by the time they got there, they’d be too damn cold to remember why the hell they were going there in the first place. The intended victim would offer them a shot of warm whiskey and a nice slab of elk meat. Then they’d agree to do it again next year. Murder rate zero. Temperature zero. Michael Moore overrated. The film should have given us the statistics for violent crimes in general, and you would probably see that Americans have killed more Canadians than the current total living there today.

Bowling For Columbine is also meandering and incoherent. It opens one conspirist thread after another without following any of them to their semi-logical conclusions. Moore is like a small child trying to get what he wants. If one approach isn’t working, try another, then another. Just keep trying. It’s the NRA’s fault. Well then it’s the government’s fault. Okay, it’s Kmart’s fault. Fine. Dick Clark is obviously behind everything.

But Moore does offer many great insights of the kind only film can provide. For example, I now know our government always supports the wrong side in ‘those war torn countries’ as conclusively proven by video montage. While I have no trouble trusting politicians to screw up even the simplest of tasks—installing the right dictators, bombing pharmaceutical plants, vinyl siding—I seriously doubt that is why Dylan Harris and James Klebold shot a bunch of their classmates. They shot them because they were two very disturbed people—oh, and because of Grand Theft Auto. But disturbed children is hardly a new occurrence. How they were able to get the guns so easily is definitely the good question. But the NRA is what it is, and everyone knows it. Exposing the NRA is about as enlightening as a speech on the evils of terrorism. A much fresher target would be Capital Hill. Obviously, any legislator who votes in favor of assault weapons is a complete assrack. Clark, Heston and, for that matter, Kmart are simply playing by the rules which weaker men have created. Moore should have found those men and questioned them individually—each and every one.

In the final segment, Moore does well to point out that the reason a six year old was able to get a gun and bring it to school and shoot another six year old is because his home life was screwed up. His mother had been evicted and the two of them were staying with the boy’s uncle. The uncle was irresponsible to leave a gun lying around the house. The gun, however, was not an AK-47. Canadians, even at this very moment, are leaving their doors unlocked. The last time the uncle left his door unlocked, his T.V. and $400 were stolen. $400 is how much the uncle makes in a week. He doesn’t give a damn about the NRA. He just doesn’t want his T.V. stolen again, or at least he wants to shoot someone for trying. He was stupid to leave the gun unlocked with the child at home. But wait. Why are we leaving a six year old alone at home period?

The film seems to want to blame the child’s problems on the fact that his mother was enrolled in Welfare to Work programs. Moore even tries to blame Dick Clark because his business associate happened to be involved with Welfare to Work. Now I enjoy seeing Dick Clark made uncomfortable as much as the next guy, but welfare policies are no more to blame than Hollywood or my indiscriminate sexual binges for the tragic number of single-parent families living in poverty. Perhaps the next time the mother is evicted, she can stay at Michael Moore’s house, where the fridge is well stocked, laughs come by the barrel, and the guns are safely in the hands of Moore’s bodyguards.

I do not have a problem with Michael Moore holding strong political views and expressing them through film. I do have a problem with Moore hijacking the documentary film style to gain instant trust, and then steering it to a place where logic and fair play are nowhere to be found. At least Oliver Stone bothers to craft his fantasies into a bad narrative.

|

fool me once, shame on you

|

Michael Moore's Roger and Me (1989) promises at first to be a model essay-film. The filmmaker sets up, in the first twenty minutes, a very strong, beguiling autobiographical narrator: we see his parents, the town where he grew up, his misadventures in San Francisco cappuccino bars. Then, disappointingly, Moore phases out the personal side of his narrator, making way for a cast of 'colorful' interviewees: the rabbit lady, the evicting sheriff, the mystic ex-feminist, the apologist for General Motors. True, he inserts a recurring motif of himself trying to confront Roger Smith, GM's chairman, but this faux-naif suspense structure becomes too mechanically farcical, and in any case none of these subsequent appearances deepen our sense of Moore's character or mind.

It is as though the filmmaker hooked us by offering himself as bait in order to draw us into his anticorporate capitalist sermon. The factual distortions of Roger and Me, its cavalier manipulations of documentary verisimilitude in the service of political polemic, have been analyzed at great length. I still find the film winning, up to a point, and do not so much mind its 'unfairness' to the truth (especially as the national news media regularly distort in the other direction) as I do its abandonment of what had seemed a very promising essay-film. Yet perhaps the two are related: Moore's decision to fade out his subjective, personal 'Michael' seems to coincide with his desire to have his version of the Flint, Michigan, story accepted as objective truth. — Phillip Lopate

|

|

And the question I want to ask is: who's selling it?

|

|

But what does her sad story have to do with Hiroshima and the bomb? Would not some other psychosexual story of deprivation be just as relevant to the horrors of war if it were set in Hiroshima? It would seem so. However, the setting itself explains another aspect of the film's strong appeal, particularly to liberal intellectuals. There is a crucial bit of dialogue: "They make movies to sell soap, why not a movie to sell peace?" I don't know how many movies you have gone to lately that were made to sell soap, but American movies are like advertisements, and we can certainly assume that indirectly they sell a way of life that includes soap as well as an infinity of other products. But what makes the dialogue crucial is that the audience for Hiroshima Mon Amour feels virtuous because they want to buy peace. And the question I want to ask is: who's selling it? — Pauline Kael

|

- Gunman wounds 20 at Montreal college 9/14/06

Crime In New Zealand

Movies

Home