— Mia Fineman

John Currin

Other Artists

Home

by Mia Fineman for Slate

Almost every art season, there's one show courageous, compelling, or contentious enough to get everybody talking—like "Sensation," the controversial exhibition of Young British Artists at the Brooklyn Museum, or the Guggenheim's populist resurrection of Norman Rockwell. This year, the name on everybody's lips is John Currin, whose midcareer retrospective recently arrived at the Whitney Museum. By now, the major critics have weighed in on Currin's slyly satirical, figurative paintings, and the reviews have been unusually enthusiastic. There are some wildly different ideas about exactly what Currin is up to—New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman sees him as "a latter-day Jeff Koons" trafficking in postmodern irony while Peter Schjeldahl at The New Yorker finds him a blissfully sincere artist tapping into the timeless values of "mystery, sublimity, transcendence." But everyone is unanimous about one thing: John Currin can paint.

In almost every review, Currin's technical skill is acknowledged with a kind of breathless wonder. And to be sure, lately he has adopted a suave, Old Master-ish style, rendering the smooth, luminous skin of his nudes with real conviction—a marked departure from the intentionally crude technique of his earlier paintings. But this critical fixation on Currin's painterly technique raises the question: Why are we so surprised that a successful contemporary painter is good at putting pigment on canvas?

In part, the answer lies with the shifting tides of artistic fashion. The story of Currin's rise to prominence generally begins in the early '90s, when political correctness held sway in the art world and highly visible exhibitions like the Whitney Biennial were filled with photography, video, and installation art dealing with politics and issues of identity. Painting—figurative painting in particular—was conspicuously absent. Currin, who had recently completed his M.F.A. at Yale University, was living in Hoboken, N.J., and trying to figure out how to break into the New York art world. As he tells it, he realized that the best way to stand out from the crowd of aspiring young artists was to do the thing nobody else was doing. So, he started making modest, easel-sized paintings, mostly portraits of young women loosely based on high-school yearbook photographs. "You get a lot of attention if you just play it straight," he said recently.

And he was right. By the late '90s, critics were pointing to a re-emergence of the figure in painting, crediting Currin along with a few other young artists like Lisa Yuskavage, Elizabeth Peyton, and Jenny Saville. The problem with this story is that figurative painting never really went away; it just retreated to the margins for a while. Artists who were interested in traditional technique gravitated toward places like the New York Academy of Art, which bases its curriculum on the study of the human figure and mastery of the painter's craft. Highly skilled representational artists like Vincent Desiderio (whose work you see in this slide), Bo Bartlett, Richard Maury, Odd Nerdrum, and Wade Schuman exhibited their work in New York galleries throughout the '90s. These painters weren't contrarians like Currin; it was just that these were the kind of paintings they wanted to make.

Some of these artists are now understandably puzzled by Currin's sudden rise to fame—and vexed by critics' worshipful fetishization of his technique. "They're nice paintings," one of them confided to me recently. "But I don't look at them and think, 'Wow! How did he do that?' " Currin does paint well and with a physical confidence that suggests that he really enjoys what he's doing. He likes to vary his handling, shifting from smooth, invisible brushwork to thick, oatmealy impasto on a single canvas; he gives his colors depth and dimension by applying paint in semitransparent layers—allowing the red to show through a brushy white surface, for example. But these techniques are part of the standard repertoire of any academically trained painter or illustrator. Currin has encouraged critics' characterization of him as a new Old Master, presenting himself in interviews as a proud reactionary driven by devotion to the formal demands of his craft. Ultimately, though, the critical focus on Currin's "technical virtuosity" is a red herring; his technique is notable mainly because of lowered expectations in the most fashionable quarters of the art world.

What really makes Currin's work interesting—and hard to dismiss—is the compelling weirdness of his imagery. He draws on an eclectic range of sources, both high and low, from '60s girlie magazines like Modern Man to Tiepolo, Cranach, and Courbet. If you know your art history, it's a lot of fun to parse the references. In his review of the Whitney show, for example, Kimmelman points out that while Nude on a Table immediately brings to mind Mantegna's famous Dead Christ, the actual source is a more obscure painting of the same subject by Annibale Carracci. This art-historical guessing game may not add up to much in the end, but as Schjeldahl says in his review, "It is pleasant to know things."

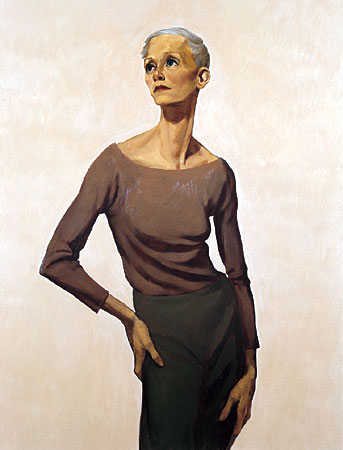

Aside from his erudition, Currin is also a masterful provocateur. For his first solo show at the Andrea Rosen Gallery in 1992, he presented a group of acerbic fantasy portraits of aging Park Avenue doyennes rendered in a pared-down, linear style that did the job without calling too much attention to itself. In the press release, Currin described them as "paintings of old women at the end of their cycle of sexual potential … between the object of desire and the object of loathing"—a deliberately sexist barb aimed at the "politically correct" art establishment. ("I meant it to sound mean. And I meant it to sound harsh," he later admitted.) Kim Levin, a critic for the Village Voice, took the bait. "Boycott this show," she wrote, virtually guaranteeing a minor stampede of curious readers heading downtown to see what the fuss was about.

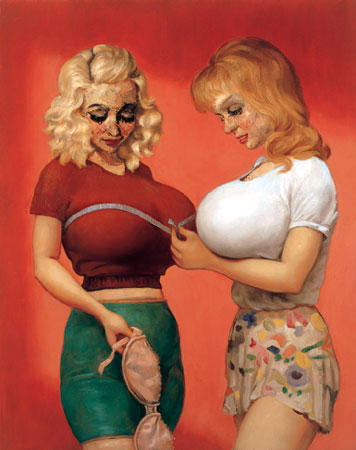

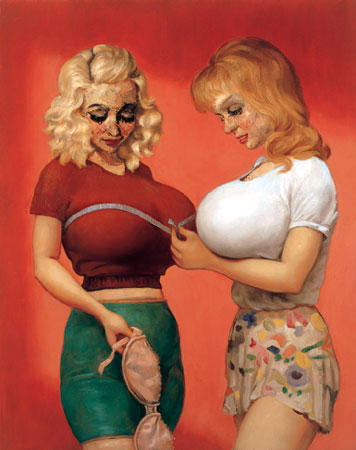

Currin's response to Levin's outrage was something along the lines of: "You want sexism? I'll give you sexism!" A few years later he presented an instantly notorious group of paintings of women with basketball-sized breasts and faces done in craggy impasto acting out various soft-porn scenarios. Crass jokes rendered in oil on canvas, they are ostentatiously "bad paintings" done in the defiantly ironic mode of high-concept kitsch. Though the reviews were tepid, Currin got a big thumbs-up from Juggs magazine, which applauded him for "paying attention to the worthy theme of big tits."

Of course, men don't fare much better in Currin's paintings, as his supporters often point out. Especially in his early work, men appear as fey, bearded, foppish playboys with big sad eyes who look like they were pieced together from a grab bag of half-remembered features. Most critics point to Currin's men as evidence of his equal-opportunity animus. But even though Currin's men may seem pathetic, they inhabit a porn-fantasy world where unattractive, goatlike guys still manage to get the babes. In Lovers in the Country, for instance, a bearded Lothario in a double-breasted blazer holds an enormous pipe and contemplates his conquest of the luscious blonde on his arm—who, incidentally, has dropped out of a Tiepolo ceiling panel at the Met. (Hey, it is pleasant to know things!)

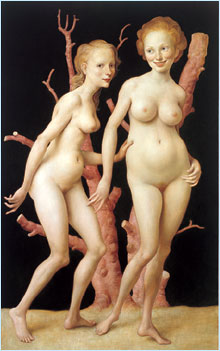

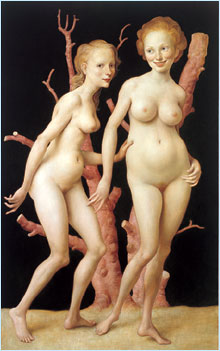

With his sinuous, round-bellied nudes of 1999, Currin shifted away from the jokey, lowbrow subjects of his earlier work and toward a chaster rehashing of the Great Tradition. The inspiration for these paintings, he says, was his wife, the sculptor Rachel Feinstein, whose wide-set eyes and angelic smile appear repeatedly in his work. The art-historical reference is to the 16th-century German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder, who turned out playfully erotic mythological scenes populated by coquettish nymphs, which charmed the provincial aristocracy of his day, much as Currin's work charms the Connecticut collectors of ours. In the last few years, a painting by Currin has become the trophy of choice in Westchester living rooms, sending auction prices through the roof. (Last spring at Sotheby's, a work from 1995 sold for an astounding $427,500.)

Like any artist whose livelihood depends on the whims of people less fabulous than himself, Currin is driven to find ever more clever ways of biting the hand that feeds him. In his recent genre paintings, he conjures arch vignettes from the everyday lives of the haute bourgeoisie: a man and woman drinking white wine and laughing too hard in a restaurant in Park City, Utah; a couple of gay men in their kitchen making homemade pasta; three young wives in a Westchester living room sipping martinis and puffing cigars after brunch. As satires, the paintings are flaccid and familiar. They evoke the sinister emptiness of suburban life without really showing us anything we haven't seen before—whether in a New Yorker cartoon or in popular films like Happiness and The Ice Storm. What Currin offers is not social critique but satire lite: teasingly familiar images of upper-middle-class life overlaid with a veneer of art-historical seriousness. Simultaneously snide and ingratiating, the paintings sneer at the social milieu of the art-viewing public while appealing to individual viewers' vanity and erudition—which may account for the work's broad popularity.

The strange thing is that for all his provocations and contrarian tendencies, Currin is oddly risk-averse as an artist—or maybe he's just well-defended. It's not that he doesn't take risks—he paints what he likes to paint, even if it means weathering accusations of misogyny, sexism, ageism, and homophobia. But he also injects just enough irony into his work to inoculate it against the possibility of debilitating failure. Because when a figurative painting goes wrong, the result can be really embarrassingly bad. When one of Currin's paintings goes wrong, his sly humor, perversity, and bad-is-good sensibility come running to the rescue. All of which makes Currin's work easy to like, but hard to love. — Mia Fineman

John Currin Other Artists Home